The Lexicon of Labor: How Appalachian Vocabularies Reflect a Working Life

The Appalachian Mountains. A place etched in the American imagination with images of rugged individualism, close-knit communities, and a quiet resilience born of hard work. But beyond the breathtaking vistas and the folk music, lies a linguistic landscape as unique and compelling as the mountains themselves. It's a landscape shaped not just by geographical isolation but, crucially, by the ceaseless toil of generations—a lexicon of labor, deeply intertwined with the rhythms of agriculture, mining, and the countless other occupations that defined Appalachian life. These aren't just words; they're echoes of a working life, a testament to the ingenuity and spirit of the people who shaped this region.

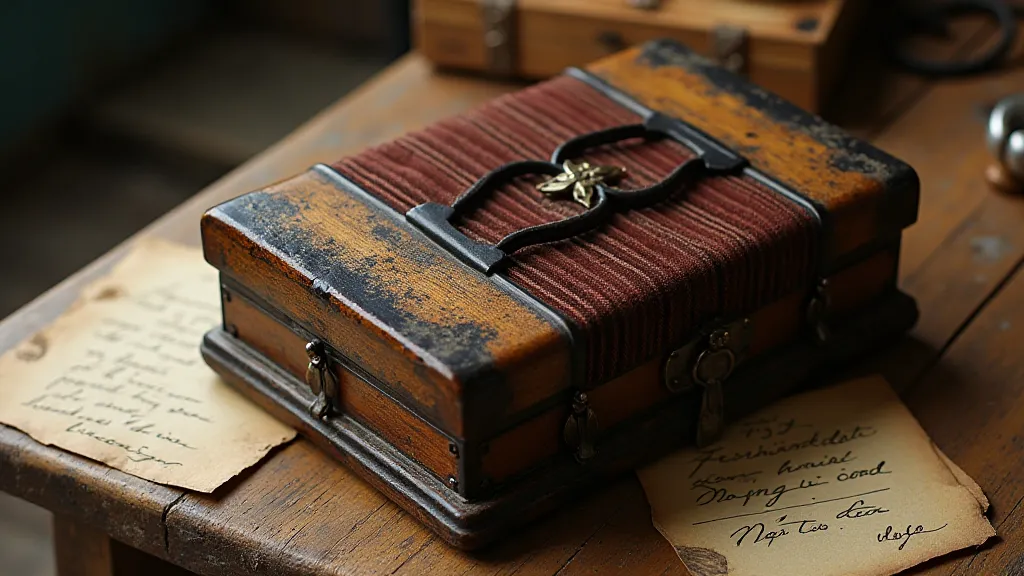

Growing up, I heard words I couldn’t find in any dictionary. My grandfather, a coal miner for over fifty years, spoke in a way that seemed to carry the dust and grit of the mines within it. He’s gone now, but I still hear his voice, painting vivid pictures with phrases like “witchin’ for water” – a practice of divining water sources with a forked branch, essential for survival and farming – or describing a particularly tough patch of land as “stubborn as a mule.” He's the reason I'm so fascinated with Appalachian dialects; they’re more than just colorful expressions—they’re living embodiments of a culture shaped by necessity. He often explained seemingly simple phrases in ways that were nuanced and complex, revealing the depth of meaning embedded in the Appalachian vernacular. Sometimes, understanding the meaning required delving into the unspoken rules and cultural assumptions that underpinned everyday communication – a world where “yes” and “no” often held far more complicated implications than they might elsewhere.

The Roots of a Working Vocabulary: Agriculture and the Land

For centuries, agriculture formed the bedrock of Appalachian life. The steep terrain dictated a subsistence farming style, requiring innovative techniques and a deeply intimate understanding of the land. This translated directly into the vocabulary. Words like “ramshackle” – often used to describe a barn or shed constructed from salvaged materials – speak volumes about the resourcefulness demanded by the environment. “Hollar,” a corruption of “hollow,” described the narrow valleys where farms were carved out of the mountainsides. The term “poke” – meaning a bag or sack – derived from the German “Pocke” and was a ubiquitous term for carrying crops or supplies. Imagine the labor involved; each "poke" a testament to a harvest earned through sweat and dedication. “Sassafras” wasn’t just a tree; it was a source of medicine, flavoring, and even a makeshift tea during lean times. The very act of conveying meaning involved a complex interplay of direct and indirect statements; Appalachian communication often favored nuance and subtlety, a characteristic explored further in discussions about Beyond 'Yes' and 'No': Appalachian Forms of Indirect Negation.

Consider the vocabulary surrounding livestock. A “kit” was a young rabbit, a "grinner" a young pig. Each term painted a picture of a living, breathing connection to the animals that sustained a family. The language reflected not just the work itself, but the inherent respect and dependency on nature’s bounty. The rhythm of the seasons resonated in every word. The understanding of natural processes and the ability to describe them with precision, often using uniquely crafted terms, was essential for survival.

The Coal Fields and Their Echoes

The advent of coal mining in the 19th century profoundly reshaped Appalachian society and left an indelible mark on its language. Words became tools for survival, imbued with danger and a shared understanding of the underworld. "Bolting" described the process of securing the mine roof, "slate" referred to the shale rock that often plagued miners, and "gob" was the broken coal left behind after the main seam was extracted. “Scrip” – a form of company currency – represented a complex and often exploitative system that tied miners and their families to the company store. Even simple terms took on new meaning. “Black lung” – a devastating respiratory disease caused by coal dust – became a constant, looming threat, woven into the fabric of miners' lives and their conversations. The harsh realities of the mines fostered a distinct mode of expression, one that blended stoicism with a dark and often self-deprecating humor.

The isolation of mining communities fostered a unique camaraderie, expressed through a shared dialect and a vocabulary steeped in the realities of their profession. Phrases like “to be on the slate” – meaning to be in debt – spoke to the precarious financial situations many miners faced. The constant risk bred a stoicism and a dark humor, which found expression in idioms that reflected the challenges of underground labor. It’s difficult to fully appreciate the weight of these words without understanding the context of hardship and danger that defined so many lives. The way miners communicated, often indirectly, to avoid causing offense or revealing vulnerability, adds another layer of complexity to understanding Appalachian vernacular.

Craftsmanship and the Language of Creation

Beyond agriculture and mining, the Appalachian Mountains have always been a haven for skilled craftspeople. The isolation fostered self-sufficiency, and the need to repair and build spurred innovation. The language surrounding these crafts is equally rich and evocative. Terms like “hewn” (to shape with an axe) and “riven” (to split along the grain) paint a picture of hand-labor and meticulous attention to detail. The act of creation, of shaping raw materials into something useful and beautiful, was not just a task; it was a form of storytelling. The names given to tools and techniques often reflected a deep respect for the materials being worked and the skills required to transform them.

Think of the old-time fiddlers, the blacksmiths forging horseshoes, the woodcarvers transforming blocks of wood into intricate works of art. The terms they used – "drawknife," "chisel," "plane" – weren’t just tools; they were extensions of their hands and minds. These skills were passed down through generations, carried within the lexicon, imbued with a sense of pride and tradition. The quiet hum of a drawknife or the rhythmic tapping of a chisel resonated with a history of ingenuity and perseverance. Often, the transmission of this knowledge wasn't through explicit instruction, but through observation and imitation, a silent passing down of skills that shaped the region’s cultural identity.

Preserving the Echoes: Why These Words Matter

As Appalachian culture has increasingly come into contact with mainstream American English, many of these unique terms are slowly disappearing, relegated to the realm of memory and family lore. The shift towards more generalized language risks erasing a vital piece of Appalachian identity. It's more than just about preserving words; it's about preserving the stories they tell, the values they represent, and the history of a people who have persevered through hardship and celebrated the simple joys of life. Maintaining the integrity of these specialized terms—like those used in traditional music repair—becomes a crucial element in safeguarding cultural heritage.

Listening to my grandfather’s stories, hearing him use those forgotten words, I realized that the Appalachian dialect isn't just a linguistic quirk; it's a living, breathing record of a working life, a testament to the enduring spirit of a people. It’s a language forged in the fire of necessity, tempered by hardship, and bound by a deep and abiding connection to the land. We owe it to future generations to keep these echoes alive, to listen carefully to the stories they tell, and to celebrate the rich and vibrant cultural heritage of the Appalachian Mountains. The nuanced and indirect communication styles characteristic of Appalachian culture, as illustrated by The Echo of 'Haint': Ghosts in Appalachian Grammar, further underscore the complexity of preserving this unique linguistic landscape.